Tech

Big Tech’s New Adversaries in Europe

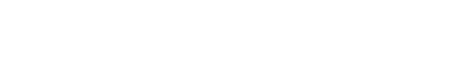

If the past five years of EU tech rules could take human form, they would embody Thierry Breton. The bombastic commissioner, with his swoop of white hair, became the public face of Brussels’ irritation with American tech giants, touring Silicon Valley last summer to personally remind the industry of looming regulatory deadlines.

Combative and outspoken, Breton warned that Apple had spent too long “squeezing” other companies out of the market. In a case against TikTok, he emphasized, “our children are not guinea pigs for social media.”

His confrontational attitude to the CEOs themselves was visible in his posts on X. In the lead-up to Musk’s interview with Donald Trump, Breton posted a vague but threatening letter on his account reminding Musk there would be consequences if he used his platform to amplify “harmful content.” Last year, he published a photo with Mark Zuckerberg, declaring a new EU motto of “move fast to fix things”—a jibe at the notorious early Facebook slogan. And in a 2023 meeting with Google CEO Sundar Pichai, Breton reportedly got him to agree to an “AI pact” on the spot, before tweeting the agreement, making it difficult for Pichai to back out.

Yet in this week’s reshuffle of top EU jobs, Breton resigned—a decision he alleged was due to backroom dealing between EU Commission president Ursula von der Leyen and French president Emmanuel Macron.

“I’m sure [the tech giants are] happy Mr. Breton will go, because he understood you have to hit shareholders’ pockets when it comes to fines,” says Umberto Gambini, a former adviser at the EU Parliament and now a partner at consultancy Forward Global.

Breton is to be effectively replaced by the Finnish politician Henna Virkkunen, from the center-right EPP Group, who has previously worked on the Digital Services Act.

“Her style will surely be less brutal and maybe less visible on X than Breton,” says Gambini. “It could be an opportunity to restart and reboot the relations.”

Little is known about Virkkunen’s attitude to Big Tech’s role in Europe’s economy. But her role has been reshaped to fit von der Leyen’s priorities for her next five-year term. While Breton was the commissioner for the internal market, Virkkunen will work with the same team but operate under the upgraded title of executive vice president for tech sovereignty, security and democracy, meaning she reports directly to von der Leyen.

The 27 commissioners, who form von der Leyen’s new team and are each tasked with a different area of focus, still have to be approved by the European Parliament—a process that could take weeks.

“[Previously], it was very, very clear that the commission was ambitious when it came to thinking about and proposing new legislation to counter all these different threats that they had perceived, especially those posed by big technology platforms,” says Mathias Vermeulen, public policy director at Brussels-based consultancy AWO. “That is not a political priority anymore, in the sense that legislation has been adopted and now has to be enforced.”