Gambling

How Malta’s economy feeds off European gambling addicts

Peter* lost more than a million euro in ten years, hiding his addiction from his family. The birth of his first child was a “wake-up call”: “What am I doing?” At that point, he had debts of around €300,000, he said.

The Austrian player promised himself he would quit, but he relapsed, sinking deeper into his addiction.

His drug of choice? Gambling. Every day, the first thing he would do when he woke up was look at his balance. “Maybe some miracle has happened, and there is money – you often get a bonus,” he said, referring to free credit given to gamble.

“And your mood depends on that. You are either in a good mood or in a bad mood, and of course, there are a lot more of the days where there’s nothing or where you try to win money back, gamble, lose,” he recalled.

Every day would be a tragedy, he said, with his health severely suffering too. At some point, he started drinking heavily, but even before that, he struggled.

“I had headaches so often, I couldn’t sleep at night, I had indigestion. My head was going crazy. You just notice that everything has such an extreme effect on the body,” he said.

But the worst part was his mental health: “What it does to the psyche is terrible. It’s just so hard to describe when you’re so depressed, and your mood is based on your bank balance.”

While Peter lives, works, and gambles in Austria, the company he lost his money to is licensed in Malta. The country has become a breeding ground for cases like Peter’s. With around 10% of the world’s online gaming companies registered in Malta, it is the epicentre of European online gambling and betting, locally known as iGaming.

Hundreds of casinos are registered on the island, but they largely operate out of sight. Out of 316 gambling companies registered with the Malta Gaming Authority (MGA), only four are land-based. The remaining casinos operate online, targeting players globally.

The iGaming industry is responsible for 12% of Malta’s GDP and directly employs over 13,000 people. The ripple effect reaching into related industries brings that number up to over 16,000 jobs – roughly 5.2% of Malta’s workforce, according to the MGA. The industry is even bigger than tourism, which makes up 10% of the Maltese economy.

Walking past the large office buildings in Sliema and Ta’ Xbiex, it’s easy to be blissfully unaware of the struggles that play out in homes across Europe and the rest of the world. But stories like Peter’s reveal the darker side of Malta’s gambling paradise, with players lost in a system that profits off their addiction.

Gaming Innovation Group headquarters overlooking St. George’s Bay.

Malta’s iGaming legacy

Malta became the first EU member state to regulate online gaming in 2004. At the time, Prime Minister Lawrence Gonzi recognised the economic potential of this emerging industry.

Notably, his son, David Gonzi, held shares in LB Group, an investment firm linked to the gambling sector. In recent years, former prime minister Joseph Muscat worked to attract more gambling companies to the island, striking deals that saved casinos millions.

Muscat reduced Dragonara Casino’s annual rent from €1.2 million to €500,000 for the first 15 years and extended the property lease by 64 years without a public tender, a deal quietly approved in parliament.

Suspicions were raised that Muscat’s later €11,800 monthly consultancy payments from a company owned by Dragonara’s managing director were linked to the deal.

Operators with a licence from Malta allow players from anywhere in Europe to register because of the EU’s freedom of establishment and freedom to provide services, which allow businesses to operate across borders within the EU.

Online casinos argue that these freedoms allowed them to operate in countries that didn’t offer national online gambling licences, like Germany until 2021, and even in countries that prohibited certain forms of online gambling, such as Austria.

Under EU law, gambling is an area where national regulatory exceptions are allowed to protect consumers and public health. In this case, Austria has a monopoly, while Germany now offers national licences.

In several cases, the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) has ruled that consumer protection and fraud prevention could justify cross-border gambling restrictions, even if they limited the freedom to provide services across EU borders.

However, the CJEU also ruled that Germany and Austria’s monopolies on gambling are against EU law, as they do not adequately justify the restrictions on foreign operators seeking to provide services within their borders.

The court has emphasised that while member states can impose regulations for legitimate public interest concerns, such as preventing addiction and protecting consumers, these regulations must not discriminate against operators from other EU countries.

Apart from legal considerations, Malta’s licensing process is also quick and inexpensive, offering a fast track into the European market.

The initial application fee is a mere €5,000 – countries like The Netherlands and Bulgaria have much higher application fees of around €50,000.

Malta’s tax framework is equally favourable, with a 5% tax on gambling revenue for players located in Malta and new operators enjoying the added benefit of no compliance contributions for their first year.

Other countries like Sweden and the UK also have stricter player protection mechanisms and high demands for social responsibility in place, including a national player registry.

Markets like France and Germany oblige operators to meet specific local criteria and restrictions, prohibiting certain casino games and having monthly deposit limits. Such criteria are largely lacking in Malta, making it easier to accept high rollers that bring large profits.

These policies propelled Malta’s iGaming market from €19 million in 2009 to an industry worth €1.4 billion today, the MGA stated.

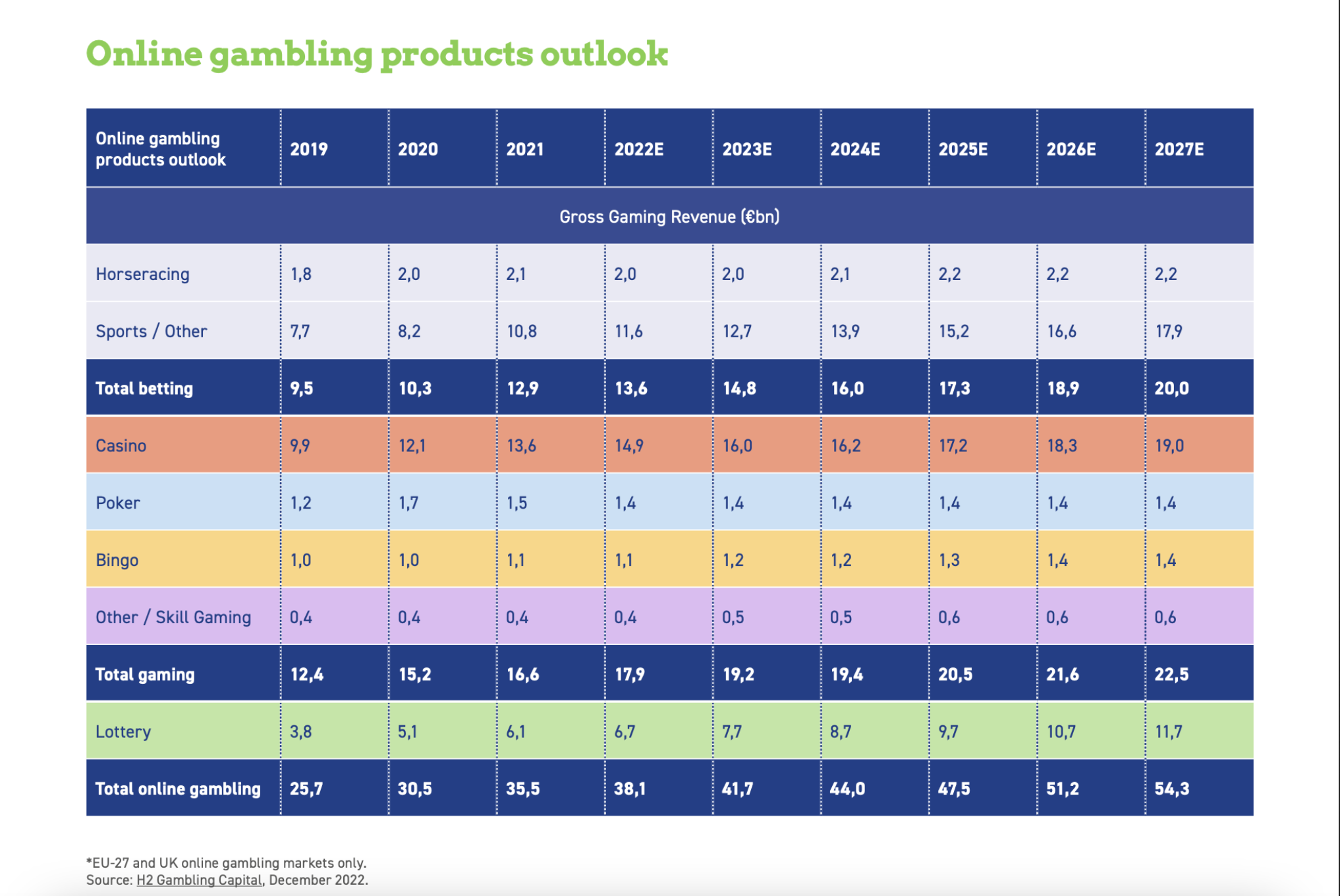

The EU and UK online gambling markets also continue to expand, valued at €35.5 billion in 2021 and projected to reach €44 billion by 2024.

Add offshore online gambling to that – operators licensed outside the jurisdictions they serve – and the European offshore gross gaming revenue is expected to hit another €6.9 billion in 2024, according to H2 Gaming Capital, a data and intelligence provider for the global gambling industry.

These figures do not reflect 100% of the illegal market, according to H2 Gaming Capital, excluding so-called grey and black markets (casinos that are either unregulated or where casinos without a national licence according to local law are illegal), meaning the full scope of unregulated gambling remains unknown.

The human toll

Peter’s experience does not exist in isolation. Problematic gambling is officially recognised as a serious mental health condition known as gambling disorder: persistent gambling behaviour leading to significant impairment or distress in personal, familial, social, educational, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.

A recent report by The Lancet indicates an estimated 80 million adults around the world suffer from the condition.

An increasing number of Europeans suffer from gambling addiction, with up to 3.4% of adults in Europe affected.

It’s difficult to get accurate numbers on gambling addiction, which is an under-researched area, and there is a lack of comparative studies across different European countries.

In 2015, according to the latest available data from the MGA, more than half of Malta’s adult population spent money on gambling, spending over €125 million annually.

While most of these bets were small, the so-called ‘whales’ lose hundreds of thousands, sometimes millions of euro.

Peter was one of those ‘whales’: “I would deposit, the balance either went up or down, usually down, then it’s gone. I deposited again, then gone again. It goes in a loop: you pay in, gamble, lose. That’s how it often went for me several times a day.”

The effects of gambling addiction – bankruptcies, divorces, and even suicides – go unseen and underreported. The Lancet reported that the rapid expansion of digital gambling platforms exacerbates the harm, as anyone with a mobile phone now essentially has 24/7 access to a casino in their pocket.

Experts expect the problem to get worse as the betting industry continues thriving in the coming years.

iGaming professionals address surge of black market in Sweden and Italy at Next.io Summit.

Sneaky strategies

Gambling may appear to hinge on luck, but the systems in place are designed to favour the house, not the player.

High-rolling gamblers, internally known as ‘whales’ according to an insider, are often lured in with enticing bonuses – extra funds credited to their accounts to encourage play. However, cashing out these bonuses can be nearly impossible; players often have to wager up to 50 times the bonus amount before they can withdraw any winnings.

Even when players do hit it big, payouts take a long time, leading many to use the credit they won to continue gambling instead. Deposits are processed in an instant, but withdrawing winnings can take anywhere from seconds to an entire week.

Peter* mentioned that payouts were sometimes “stuck in the system” for some reason, and some employees suggested that these payout delays were deliberate strategies aimed at coaxing players back into gambling before they can collect their winnings.

Operators attribute these delays to necessary compliance checks, anti-money laundering regulations, or “bonus abuse investigations”. The MGA also states that anti-money laundering checks, wagering requirements, and external banking processes can take time.

Several foreign lawyers representing over 25,000 European gamblers allege that nearly none of their clients have been screened for sources of funds or signs of problematic gambling behaviour, known as “know your customer” procedures, despite many struggling with gambling addiction.

One iGaming employee confirmed players can lose large sums of money without triggering any additional checks while reviews often occur when someone attempts to withdraw a large sum, especially after winning a jackpot – making them a ‘shark’.

When an unusual transaction occurs, it is reported to either the compliance department or the Financial Intelligence Unit (FIU), yet the player is not immediately blocked from further gambling. As long as the casino reports the incident, it remains legally shielded from consequences.

Responsible gambling teams only step in when they see clear signs of financial distress, such as players depleting their savings or selling off their houses.

Self-exclusion systems, intended to support individuals seeking to quit gambling, often prove inadequate due to a lack of cross-operator coordination.

While players can impose a self-exclusion period of up to 12 months on themselves, this measure only applies to the platform from which they have excluded themselves – they can still easily switch to another casino. There is no system in place to prevent them from doing so. In countries like Sweden, a national registry ensures players are blocked from all operators simultaneously.

The MGA argues that such a national self-exclusion system is ineffective as unregulated online casinos and casinos licensed in other jurisdictions exist, which means players can gamble on those platforms with fewer safeguards in place. The Authority advocates for the standardisation of responsible gambling policies instead.

Even in countries where gambling is banned, players aren’t always safe. At least one company operates in Switzerland without a licence, circumventing government blocks by providing new, untraceable websites.

They create mirror sites (copies of the company’s real websites) with domain names like “12345.com” and direct players there. When these sites are blocked by Swiss authorities, they simply create a new one.

The new domains are often not given out in writing but communicated via phone calls to avoid evidence of illegal operations.

While the MGA acknowledges potential issues with operators circumventing gambling bans via mirror sites, it emphasises that compliance is the operators’ responsibility. The Authority states it is committed to investigating violations and enforcing regulations in the gaming industry.

Malta’s shield: Bill 55

Foreign and Maltese lawyers argue that targeting markets where Maltese gaming companies do not have a local licence to operate is illegal.

An Austrian law firm and a German lawyer representing gamblers accused Malta of undermining the rule of law in the EU by changing its gaming regulations to shield Maltese companies operating without proper licences in Austria and Germany.

In Austria, there is a state monopoly on gambling, and in Germany, a company needs to apply for a local licence.

Despite court rulings in these countries ordering refunds to players, Malta blocks the enforcement of these judgments, which they argue violates EU citizens’ rights.

CasinoBeats Summit at the InterContinental Hotel Malta in May 2024.

In June 2023, Malta’s parliament approved amendments to the Gaming Act through Bill 55 – now Article 56A of the Gaming Act – which shields online gambling companies from foreign lawsuits. The law prevents foreign judgments – such as those from Germany and Austria – from being enforced in Malta if they conflict with Malta’s public order.

Under Article 45 of EU law, a Member State can refuse to enforce a foreign judgment if it is “manifestly contrary to public order”. In Malta’s case, it is argued that enforcing judgments against its iGaming industry would harm its economy, as online casinos account for 12% of the GDP – enforcing such rulings would devastate the economy.

The MGA states that Article 56A is “not enacted to shield these companies from legal action before other European courts” but rather a provision that clarifies Malta’s long-standing public policy on gaming. However, in practice, the article means that players who win legal cases against Maltese companies often cannot recover their losses.

Austrian lawyer Karim Weber, a specialist in gaming law who, according to his own statement, has represented and represents players in more than 13,000 claims against online casinos, faces significant challenges due to Article 56A. His clients, who have usually lost tens of thousands and even hundreds of thousands of euro, often win legal judgments in Austria but rarely see their money again because Malta blocks enforcement.

For around 200 execution proceedings filed, the process is slow and complicated, Weber says. Typically, an EU court judgment would be enforced directly across member states, but in this case, claimants have to initiate a new legal process through the Maltese courts to recover funds.

Although companies sometimes agree to pay settlements, the opposing party initiates proceedings to block the enforcement when the claimant attempts to retrieve the money, arguing that the Austrian judgment disrupts Malta’s public order.

This has led to lengthy legal disputes, with court hearings spaced months apart and progress dragging on for years.

“Some people lost their homes. Some people were homeless from gaming. They lost their work, they lost big companies, they lost their inheritance,” Weber explains. “There needs to be a decision because this non-decision is not justice at all.”

Peter has been doing better for about a year. He has been diagnosed with a pathological gambling addiction. He says he has gotten more than €100,000 back through court cases, but his debts are still in the hundreds of thousands.

Peter* has chosen to remain anonymous for this interview to protect his privacy.

This investigation is supported by a grant from the IJ4EU fund. The International Press Institute (IPI), the European Journalism Centre (EJC), and any other partners in the IJ4EU fund are not responsible for the content published or any use made of it. The Shift has received no funds from this investigation and is publishing the report to support independent work.