Bussiness

News analysis: EU needs to experiment with new R&I funding mechanisms, Heitor report says

The way the EU funds research and innovation isn’t really working, and the European Commission urgently needs to experiment with new ways to do it, according to a new influential report on the future of the EU’s research and innovation framework programmes published today.

The report, prepared by a group of 15 experts led by former Portuguese science minister Manuel Heitor, is stuffed to the brim with ideas for new councils, efficiencies and restructurings.

But beneath these concrete proposals, there’s a deeper, damning message: “Disruptive, paradigm shifting research and innovation”, the report says, the kind that remakes entire economies or societies, is “unlikely to be fostered by conventional procedures and programmes that are prevalent in the EU today”.

In a stark admission, the report says that most EU, and indeed national, research programmes support only “incremental scientific advances, development and innovation” rather than paradigm shifts.

Agencies across the world are experimenting with new types of funding and the EU must join this wave, or risk being left behind, Heitor warned in an interview with Science|Business. “There is a need for Europe to lead this process,” he said.

The report wants the EU to “immediately” establish an “experiment unit” to test out “new programmes, evaluation procedures and instruments”.

Based in the Commission’s Directorate-General for Research and Innovation, this unit needs a “significant budget” and “maximum flexibility” from normal rules to allow it to rapidly toy with new methods of funding, the report demands.

The EU shouldn’t wait until the next framework programme to get cracking, Heitor stresses. “We have three years of Horizon Europe […] to test these new things,” he said.

This is part of a broader narrative that research is failing to deliver, not just in Europe, but globally.

“The science system, for all of its rhetorical promise, has failed at that downstream end to yield the kind of advances at the speed, at the quantity that perhaps had been promised, expected, hoped,” said James Wilsdon, executive director of the London-based Research on Research Institute, and professor of research policy at University College London.

Over the past decade, there have been a drumbeat of warnings to this effect.

A major study released last year concluded that “papers and patents are increasingly less likely to break with the past in ways that push science and technology in new directions”.

And a paucity of new inventions has led to stagnation for the average person, so goes the argument. The US economist Robert Gordon, for example, has argued that since the 1970s, there have been far fewer life-changing (and beneficial) new technologies like the fridge, car or indoor plumbing, as the low-hanging fruit of industrial development has already been picked. Low growth is now the norm.

Fresh funding ideas

Yet partly in response to these warnings, there’s also been a flowering of experimentation with new ways to fund research and innovation.

“There is something in the air,” said Wilsdon. A dozen or more countries have launched some form of initiative into “metascience”, which, put simply, applies “scientific approaches to the management […] of the funding system,” he said.

Most of these so far have been small scale pilot schemes, he said, but hope now is that bigger, more rigorous trials can shed light on what works.

Some of these aim to give funding to more risky research proposals, like giving grant reviewers a “golden ticket” to back a proposal, even if other reviewers object.

During the pandemic, one US-based fund rolled out “Fast Grants” for researchers who urgently needed money to study Covid-19, overcoming the tediously long wait for money often endured by scientists.

The US’s 2022 CHIPs and Science Act has mandated the country’s National Science Foundation to toy with new funding and assessment ideas.

Earlier this year, the UK’s main funder, UK Research and Innovation, and the US-based foundation Open Philanthropy, put out a joint £5 million call of metascience grants to explore “more effective ways of conducting and supporting research and development”.

Related story:

Draghi report: could the EU set up its own Darpa-like agency?

Canadian agencies have also launched metascience initiatives, and there’s strong interest in metascience in Japan and China too, said Wilsdon.

And on both sides of the Atlantic, a new set of innovation-focused institutions have been set up, modelled on the US’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (Darpa), which, among other features, gives huge budgets and leeway to programme managers to back disruptive new projects.

Washington has recently established a new Arpa in health, while the UK and Germany have followed with their own Arpa-like organisations.

A range of ideas

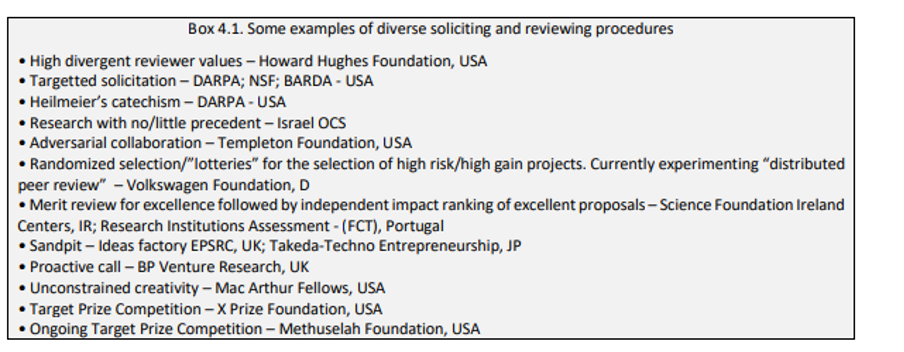

The Heitor report offers a grab-bag of ideas, ranging across the whole R&D spectrum, for the new experimental unit to try.

At the research grant level, for example, “distributed peer review” asks applicants to grant schemes to also review other proposals, in order to relieve the burden on unpaid reviewers.

The Volkswagen Foundation in Germany is currently running a trial of this idea; so far, feedback is positive, and the hope is that it will end up selecting more adventurous proposals than conventional panel review.

At the other end of the R&D process, the Heitor report also recommends aping the US-based XPrize Foundation, which offers up sometimes huge prize pots for solving challenges ranging from carbon dioxide removal to better facemasks. “Currently the EIC [European Innovation Council] has no programmes to stimulate disruptive innovation,” it says, and prizes could be an answer.

The Commission has indeed experimented with prizes in the past, and is mulling over a new tranche for renewable energy technology.

But the sums are tiny compared to what’s offered by the XPrize Foundation; one ongoing prize offers a $119 million pot for anyone who can find new ways to desalinate water (it’s funded by a foundation linked to the Saudi royal family).

Speed of the essence

This new unit needs to incorporate “fast time to funding”, the Heitor report says. Indeed, the report is shot through with the sense that the application process needs to significantly accelerate.

It takes almost a year for applications to be processed, Heitor complained to Science|Business. Horizon Europe is actually taking longer to process applications than its predecessor, Horizon 2020, according to an analysis of part of the programme released earlier this year.

The whole programme needs “a radical reform of the application system to ‘trust first/evaluate later’ and become more applicant-friendly, Commission-efficient, impact-oriented and ensure a reduced time to fund,” his report says.

The German innovation agency Sprind has explicitly tried to make grants as quick as possible, with at most four weeks between an application deadline and wiring the money. Take too long, and teams of innovators will lose momentum and commercial opportunities, the agency argues.

ARPA on the Horizon?

Heitor’s report is also the second heavyweight Brussels report in as many months to call for the EU to establish its own Darpa – or at least a kind of Darpa-inspired innovation agency.

The first was a report by former Italian prime minister Mario Draghi last month, which made an EU Arpa its top research and innovation recommendation.

Like the Draghi report, Heitor wants the EIC to begin experimenting with Arpa-type programmes. These normally give programme managers high levels of funding and discretion to back innovation projects that achieve a specific goal – backed up by strict milestones and a willingness to pull the plug on failing ideas.

If this model succeeds in the EIC, it could be rolled out to other areas of the framework programme, the report says.

But Heitor’s report also adds quite a few caveats to the Arpa idea – you already need an existing ecosystem of innovators ready to respond to problems set by the agency, it points out.

It will also not be “straightforward” to hire very highly paid, unconstrained programme managers given labour laws in EU countries, cautioned Heitor.

“The Arpa model will never work exactly in Europe, but we can adopt other things [from it],” he said.